Introduction to sigma notation

| Narration of study guide: |

What is sigma notation?

If you want to add many things together, then it would be nice to have a quick way of writing this down! This is where sigma notation comes in. Sigma notation is an indispensable tool in expressing additions of any amount of numbers (or other mathematical objects). For instance, sums of areas of rectangles are used in constructing the idea of a definite integral; one of the most important tools in mathematics. In addition, sigma notation is used in defining the multiplication of two or more matrices, which are objects that govern movement of shapes in a space. Most importantly however, sigma notation is used for counting things!

This guide introduces you to the idea of sigma notation and explains some initial properties.

A sum is the result of addition of two or more numbers. If \(a_k,a_{k+1}, \ldots, a_N\) are real numbers (where \(k\) and \(N\) are some whole numbers with \(k\leq N\)), then you can use sigma notation to write their sum as \[a_k + a_{k+1} + \ldots + a_N = \sum_{i = k}^N a_i\] where the right hand side reads ‘the sum from \(i = k\) to \(i = n\) of the elements \(a_i\)’.

The symbol \(i\) is known as the index of the sum; the index of a sum could be any letter (usually \(i,j,k,n\) but could be others!).

The number \(k\) is known as the lower bound of the sum and the number \(N\) is known as the upper bound of the sum.

Examples

Here’s some examples of sigma notation.

What is the value of \(\displaystyle\sum_{i=1}^{10} i\)?

You can use the definition above to write this out as a sum and then calculate it: \[\displaystyle\sum_{i=1}^{10} i = 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 + 7 + 8 + 9 + 10 = 55.\]

What is the value of \(\displaystyle\sum_{n=2}^5 n^2\)?

Before tackling a problem using sigma notation, it can be best to read it out loud. Here, \[\sum_{n=2}^5 n^2\textsf{ is 'the sum from $n = 2$ to $n = 5$ of $n^2$'.}\] This translates to \[\sum_{n=2}^5 n^2 = 2^2 + 3^2 + 4^2 + 5^2\] and \(2^2 + 3^2 + 4^2 + 5^2 = 4 + 9 + 16 + 25 = 54\).

What is the value of \(\displaystyle\sum_{n=1}^N n = S\)?

In this case, you’re being asked to find \(S = 1 + 2 + 3 + \ldots + N\). The following method is due to Gauss, who came up with this answer during a maths lesson at school when he was seven (hinting at the genius to follow).

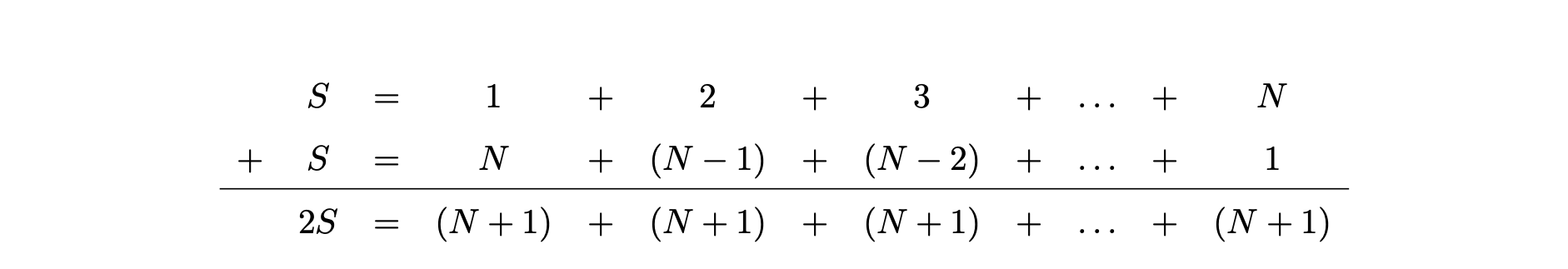

First of all, you can reorder \(S\) to write that \(S = N + (N-1) + \ldots + 2 + 1\). Adding two lots of \(S\) together gives the following:

Therefore, \(2S\) is \(N\) lots of \((N+1)\); you can write this as \(2S = N(N+1)\). Dividing both sides by \(2\) gives \(S = N(N+1)/2\).

Writing sums using sigma notation

In this section, you will learn how to do the opposite of the above. That is, given a sequence of numbers, you will learn how to write their sum using sigma notation. The central idea of this process is to recognize a pattern in the sequence of given numbers; which can be best obtained by practice! It’s best to learn this using examples.

Write \(2 + 4 + 6 + 8 + 10 + 12\) using sigma notation.

You can tell that these are the first six multiples of \(2\). So you can list these elements as \(2n\) for \(n = 1\) up to \(n = 6\). Therefore, you can write that \[2 + 4 + 6 + 8 + 10 + 12 = \sum_{n=1}^6 2n.\]

Write \(1 + 2 + 4 + 8 + 16 + 32\) using sigma notation.

These are the first 6 numbers in the sequence \(2^n\) for \(n=0\) up to \(n=5\). Therefore, you can write \[1 + 2 + 4 + 8 + 16 + 32 = \sum_{n=0}^5 2^n.\]

Write \(-1 + 2 -3 + 4 - 5\) using sigma notation.

For these types of sequences it’s useful to keep in mind the sequence \((-1)^n\), which alternates between \(1\) and \(-1\) based on whether or not \(n\) is even (in which case \((-1)^n = 1\)) and . Hence, you can write these elements as \((-1)^nn\) for \(n=1\) up to \(n=5\). Using sigma notation, it will look like this: \[\sum_{n=1}^5 (-1)^nn.\]

Properties of sigma notation

In this section you will learn about a few properties of sigma notation which means you’ll have a toolkit to manipulate finite sums.

Distributivity

The first property you’ll learn about sigma notation is distributivity. This property allows you to take constants from inside the sigma notation to outside the summation.

Let \(a_k,a_{k+1}, \ldots, a_n\) be a sequence of numbers (where \(k\) and \(n\) are whole numbers with \(k \leq n\)) and \(C\) be any constant. Then \[\sum_{i=k}^n Ca_i = C \sum_{i=k}^n a_i.\]

What is the value of \(\sum_{n=2}^5 6n^2\)?

Using distributivity, \(\sum_{n=2}^56n^2 = 6\sum_{n=2}^5n^2\). From Example 2, you know that \(\sum_{n=2}^5n^2 = 54\). Therefore, \(6\sum_{n=2}^5n^2 = 6 \times 54 = 324\).

Combining and decomposing sums

Another property of sigma notation is something called combining sums; the reverse known as decomposing sums. This allows you to write two sums in sigma notation as one sum, or to split one sum in sigma notation into two separate sums.

Let \(a_k,a_{k+1},\ldots,a_n\) and \(b_k,b_{k+1},\ldots,b_{n}\) be two sequences of numbers (where \(k\) and \(n\) are whole numbers with \(k \leq n\)). Then \[\sum_{i=k}^na_i + \sum_{i=k}^n b_i = \sum_{i=k}^n(a_i + b_i)\] and \[\sum_{i=k}^na_i - \sum_{i=k}^n b_i = \sum_{i=k}^n(a_i - b_i).\]

Note in the property above that both sequences start at \(k\) and end at \(n\). So when combining sums, the lower bound and upper bound have to be the same in both sums.

What is the value of \(\displaystyle\sum_{n=1}^6 (6n + 4)\)?

You can decompose this sum into two parts which you can work out individually. Using the above result gives \[\sum_{n=1}^6 (6n + 4) = \sum_{n=1}^6 6n + \sum_{n=1}^6 4\] and using distributivity gives \[\sum_{n=1}^6 6n + \sum_{n=1}^6 4 = 6\sum_{n=1}^6 n + \sum_{n=1}^6 4\] Using the result from Example 3, you can write that \[6\sum_{n=1}^6 = 6\cdot\left(\frac{6\cdot 7}{2}\right) = 6\cdot 21 = 126\] and that \[\sum_{n=1}^6 4 = 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 = 24\]. Therefore \[\sum_{n=1}^6 (6n + 4) = 126 + 24 = 150\].

You can notice from Example 8 that if the term inside the sum does not depend on the index of the sum, then that term is added to itself as many times as the sum determines. This is true in general, and can be thought of as a property of sums:

If the term \(c\) inside the sum does not depend on the index \(i\) in any way, then \[\sum_{i = k}^N c = (N-k)\cdot c.\]

Re-indexing

Since the lower and upper bounds in the sums have to be the same to either combine or decompose the sum, it’s often useful to be able to re-index a sum in order to do this.

Let \(\displaystyle\sum_{n=k}^Nf(n)\) be a sum, where \(F(n)\) is an expression that depends on the index \(n\). You can re-index the sum as \[\sum_{n=k}^NF(n) = \sum_{n=k+p}^{N+p}F(n-p)\] for any integer \(p\).

You can see that this is true by working out the sum. Here is an example of the power of re-indexing:

Write \(\sum_{n=1}^62n + \sum_{n=0}^52^n\) as a single sum.

First, notice that the indices of these sequences are different; this means that you will need to re-index. You can see that \(0 = 1-1\) and \(5 = 6-1\). Taking \(p = -1\) (so \(n - p = n+1\)) and using re-indexing gives \[\sum_{n=1}^6 2n = \sum_{n=0}^5 2(n-(-1)) = \sum_{n=0}^5 (2n+2).\] You can now use the combining sums property to get \[\sum_{n=1}^62n + \sum_{n=0}^52^n = \sum_{n=0}^5 (2n+2) + \sum_{n=0}^52^n = \sum_{n=0}^5 (2n + 2^n + 2).\]

In the above example, you could also re-index \(\sum_{n=0}^52^n\) instead of \(\sum_{n=1}^62n\). Give it a go!

Splitting a sum

Finally, you can express any sum as the addition of two or more sums by splitting the sum at a certain point:

Let \(a_k,a_{k+1},\ldots,a_n\) be a sequence of numbers (where \(k\) and \(n\) are integers with \(k < n-1\)). Then for any integer \(m\) such that \(k \leq m < n\), \[\sum_{i=k}^n a_i = \sum_{i=k}^m a_i + \sum_{i=m+1}^n a_i.\]

You can see that this is true by writing out the sum!

Write \(\sum_{i=10}^{100}i\) as the addition of three sums.

There are many ways to do this (can you count how many?). An example of which is:

\[\sum_{i=10}^{11} i + \sum_{i=12}^{98} i + \sum_{i=99}^{100} i.\]

Quick check problems

- What is the value of \(\displaystyle\sum_{i = 2}^{6} i\)?

Answer: The value of the above is: .

- Given \(\displaystyle\sum_{j = 1}^{100} i\), identify the index of the sum.

Answer: The index is

- You are given several statements below based on the properties of sums. Identify whether they are true or false.

The sum \(3 + 6 + 9 + 12\) can be expressed as \(\displaystyle\sum_{i = 0}^{4} 3i\) Answer: .

The sum \(-1 + 1 - 1 + 1\) can be expressed as \(\displaystyle\sum_{i = 1}^{4} -i\) Answer: .

\(\displaystyle\sum_{i = 1}^{100} i = \sum_{i = 0}^{101} i\) Answer: .

\(\displaystyle\sum_{i = 1}^{100} 6i = 6 \sum_{i = 0}^{100} i\) Answer: .

\(\displaystyle\sum_{i = 1}^{100} 9i + \sum_{i = 1}^{100} 3i = \sum_{i = 1}^{100} 27i^2\) Answer: .

\(\displaystyle\sum_{i = 1}^{100} 12i - \sum_{i = 1}^{100} 4i = 8 \sum_{i = 1}^{100} i\) Answer: .

Further reading

For more questions on the subject, please go to Questions: Introduction to sigma notation.

Version history and licensing

v1.0: initial version created 08/23 by Ifan Howells-Baines and Mark Toner as part of a University of St Andrews STEP project.

- v1.1: edited 05/24 by tdhc, and split into an introductory guide and a further topics guide (to be completed).